TV icon Loni Anderson dies at 79: a sitcom trailblazer whose fame outlived the headlines

Loni Anderson, the bright, savvy receptionist Jennifer Marlowe from WKRP in Cincinnati, has died at 79. She passed away on August 3, 2025, in a Los Angeles hospital after a prolonged illness, her longtime publicist Cheryl J. Kagan confirmed. The news arrived just two days before what would have been her 80th birthday on August 5. “We are heartbroken to announce the passing of our dear wife, mother and grandmother,” her family said in a statement.

Anderson’s turn on the CBS sitcom wasn’t just a breakout part—it was a reset for how TV treated the so‑called “blonde bombshell.” As Jennifer Marlowe, she played the office gatekeeper who was not only beautiful but also the sharpest person in the room. The role earned her two Emmy nominations and three Golden Globe nods and cemented her as a household name in late‑1970s and early‑1980s television.

Born August 5, 1945, in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Anderson came up the traditional way—regional theater, guest shots, TV movies—before WKRP hit in 1978. She drew wide notice playing Jayne Mansfield in the 1980 TV movie The Jayne Mansfield Story, holding her own opposite a young Arnold Schwarzenegger as Mickey Hargitay. But it was the radio‑station comedy that stuck. WKRP’s underdog energy and ensemble (Howard Hesseman, Tim Reid, Gordon Jump, Jan Smithers, Gary Sandy) gave Anderson room to craft a character who could turn a raised eyebrow into a punchline and a negotiation into a power play.

WKRP wasn’t a ratings monster in its first run, but it exploded in syndication. Anderson rode that wave, turning up in TV movies and series that leaned into her comedic control and on‑screen warmth. She headlined the short‑lived crime drama Partners in Crime with Lynda Carter in 1984 and later joined the hospital sitcom Nurses in the early 1990s. Through it all, the public image—glamorous, composed, unmistakable in a crowd—followed her from photo shoots to red carpets.

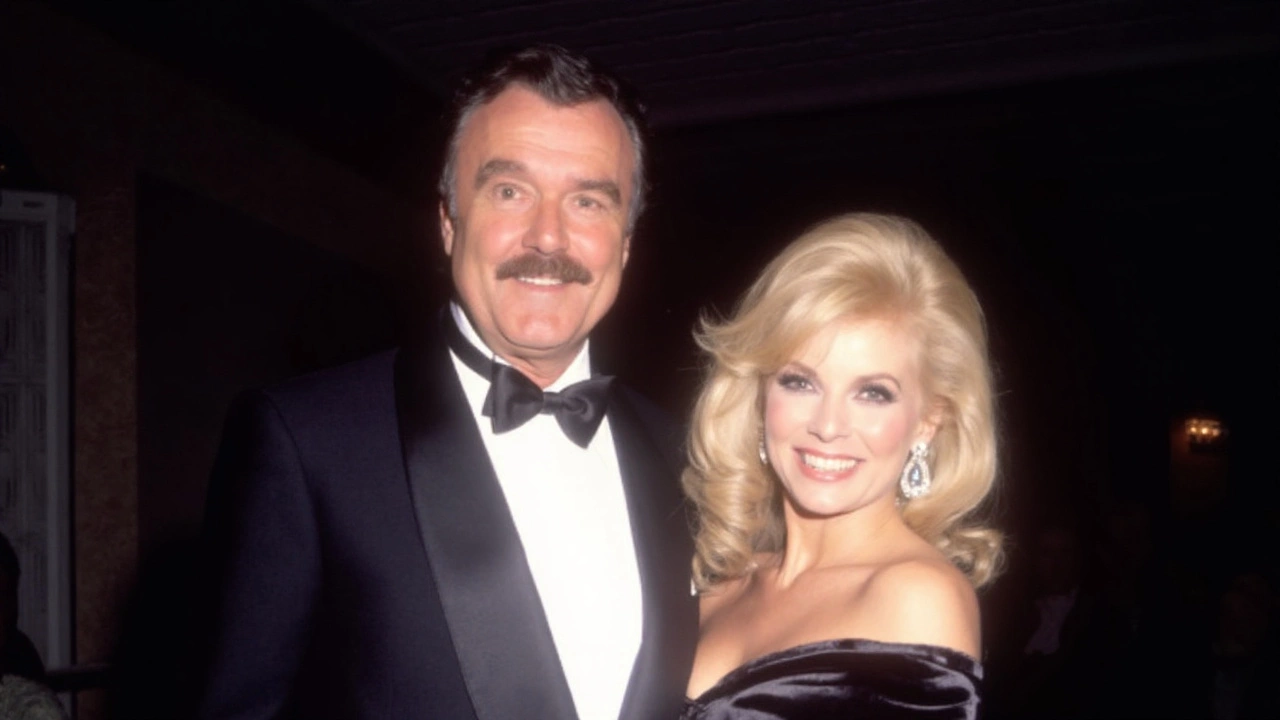

The fame also came with the intense media glare that would shadow her private life. By the mid‑1980s she was as likely to appear on a magazine cover for her look and celebrity as for a role. That attention grew exponentially once Burt Reynolds entered the picture.

Burt Reynolds, a whirlwind romance, and a breakup that defined a decade of tabloids

Anderson and Reynolds first met in 1981 on The Merv Griffin Show. At the time, she was married to actor Ross Bickell and Reynolds was involved with Sally Field. By 1982, the two were dating. Their on‑screen pairing in 1983’s Stroker Ace doubled as a showcase for their off‑screen chemistry, and soon they were one of the most watched couples in Hollywood.

They married in 1988 in Florida, keeping the guest list to roughly 65 people. Reynolds designed the 7‑carat engagement ring himself. People magazine wrote at the time that the relationship was based on “love and respect,” and for a while, that’s how it looked. The couple adopted a son, Quinton, and built a life split between work and home, with a steady churn of premieres, charity appearances, and camera flashes documenting every step.

By 1993, the tone changed. Reynolds suddenly announced the separation that June, and their divorce—finalized in 1994—consumed headlines for months and then years. It became the kind of Hollywood saga that wouldn’t quit, stretching across court filings, TV interviews, and front pages. The coverage got so relentless that Reynolds later liked to say Princess Diana sent him a note thanking him for keeping her off the cover of People magazine.

So what actually went wrong? There was no single cause, but a stack of pressures that built up and blew apart the marriage. The public record—interviews from the time and legal filings—points to a mix of clashing expectations, money worries, and personal grievances that fed on the attention.

- Financial strain: Reynolds’ investments and business ventures in the early 1990s were under stress, and his earning power dipped from its late‑1970s peak. The financial fallout lingered; he filed for bankruptcy protection in 1996. That stress bled into the marriage.

- Allegations on both sides: In public and in court documents, each accused the other of bad behavior. He criticized her spending and questioned her motives; she described a marriage marked by volatility and alleged abuse, which he denied. Neither side’s story ever fully silenced the other.

- Infidelity and trust: Interviews at the time hinted at affairs and long‑simmering resentment about fidelity. Those claims were never resolved to anyone’s satisfaction but kept the tabloids fed for years.

- Tabloid pressure: Their relationship became a spectacle. Every argument, every court date, every rumor played out in splashy headlines, turning private conflict into public theater and making reconciliation unlikely.

- Custody and support fights: The couple adopted Quinton during the marriage, and negotiations over custody, child support, and alimony dragged on. Court orders and modifications kept the legal battle alive well past the divorce decree.

Anderson outlived that storm. She kept working in television movies and series guest spots, and she rebuilt her personal life well away from the 1990s noise. She married Bob Flick, a founding member of the folk group The Brothers Four, in 2008. Friends say that marriage offered the quiet that fame rarely does.

Reynolds died of a heart attack on September 6, 2018. Their son Quinton, now in his 30s, has kept a low profile. The history between his parents never fully faded from public memory, but over time the conversation returned to the work that made them famous in the first place.

For Anderson, that legacy starts with WKRP in Cincinnati. Jennifer Marlowe wasn’t written as a punchline. She was the most competent person in a chaotic office, and Anderson played her with timing that made the jokes land and restraint that kept the character believable. In a TV landscape that often flattened women into one trait, she pushed back gently, episode by episode, until the audience knew exactly who ran that front desk and why everyone, viewers included, listened when she spoke.

Her fame also reflected a very specific kind of late‑20th‑century television stardom: built on broadcast hits, amplified by magazines, and later sustained by reruns that turned week‑to‑week viewers into lifelong fans. When syndication brought WKRP to new audiences, Anderson’s performance became a comfort watch—part nostalgia, part master class in underplaying a role many would have overplayed.

In the days ahead, expect tributes from co‑stars, comedy writers who grew up on her timing, and fans who found in Jennifer Marlowe a version of office power that didn’t need shouting. The image—the blonde hair, the dimples, the poise—was famous. The control behind it was the point. That’s why her name still lands with people who weren’t born when WKRP first aired.

Key dates in her life and career help map the story that followed her for more than four decades:

- 1945: Born in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

- 1978–1982: Breakout as Jennifer Marlowe on WKRP in Cincinnati; two Emmy nominations and three Golden Globe nominations.

- 1980: Plays Jayne Mansfield in a TV movie that widens her range beyond sitcom fame.

- 1983: Co‑stars with Burt Reynolds in Stroker Ace.

- 1988: Marries Reynolds in Florida; the couple later adopts their son, Quinton.

- 1993–1994: Separation and highly public divorce; years of legal wrangling follow.

- 2008: Marries musician Bob Flick.

- 2018: Reynolds dies of a heart attack.

- 2025: Anderson dies in Los Angeles, days before her 80th birthday.

The work remains. The stories remain. And so does the image of a woman who understood how to own a scene with a glance and a line read—then navigate celebrity at its loudest and still find a quieter life at the end of the day.